Quantum mysteries dissolve if possibilities are realities

When you think about it, it shouldn’t be surprising that there’s more than one way to explain quantum mechanics. Quantum math is notorious for incorporating multiple possibilities for the outcomes of measurements. So you shouldn’t expect physicists to stick to only one explanation for what that math means. And in fact, sometimes it seems like researchers have proposed more “interpretations” of this math than Katy Perry has followers on Twitter.

So it would seem that the world needs more quantum interpretations like it needs more Category 5 hurricanes. But until some single interpretation comes along that makes everybody happy (and that’s about as likely as the Cleveland Browns winning the Super Bowl), yet more interpretations will emerge. One of the latest appeared recently (September 13) online at arXiv.org, the site where physicists send their papers to ripen before actual publication. You might say papers on the arXiv are like “potential publications,” which someday might become “actual” if a journal prints them.

And that, in a nutshell, is pretty much the same as the logic underlying the new interpretation of quantum physics. In the new paper, three scientists argue that including “potential” things on the list of “real” things can avoid the counterintuitive conundrums that quantum physics poses. It is perhaps less of a full-blown interpretation than a new philosophical framework for contemplating those quantum mysteries. At its root, the new idea holds that the common conception of “reality” is too limited. By expanding the definition of reality, the quantum’s mysteries disappear. In particular, “real” should not be restricted to “actual” objects or events in spacetime. Reality ought also be assigned to certain possibilities, or “potential” realities, that have not yet become “actual.” These potential realities do not exist in spacetime, but nevertheless are “ontological” — that is, real components of existence.

“This new ontological picture requires that we expand our concept of ‘what is real’ to include an extraspatiotemporal domain of quantum possibility,” write Ruth Kastner, Stuart Kauffman and Michael Epperson.

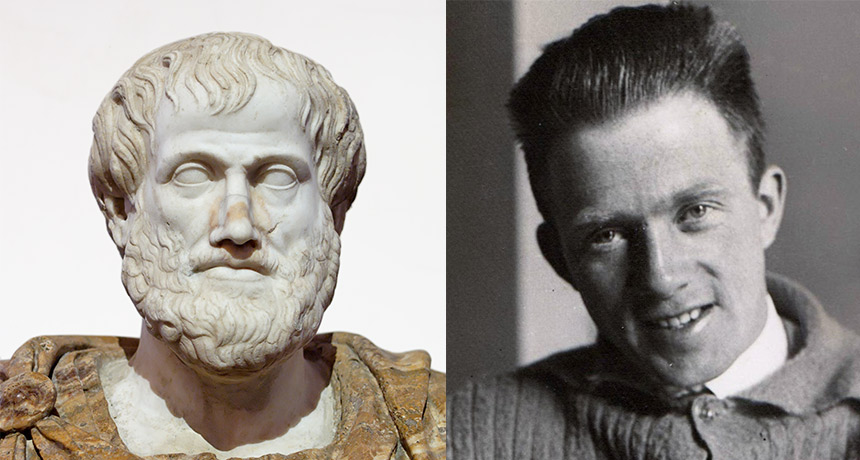

Considering potential things to be real is not exactly a new idea, as it was a central aspect of the philosophy of Aristotle, 24 centuries ago. An acorn has the potential to become a tree; a tree has the potential to become a wooden table. Even applying this idea to quantum physics isn’t new. Werner Heisenberg, the quantum pioneer famous for his uncertainty principle, considered his quantum math to describe potential outcomes of measurements of which one would become the actual result. The quantum concept of a “probability wave,” describing the likelihood of different possible outcomes of a measurement, was a quantitative version of Aristotle’s potential, Heisenberg wrote in his well-known 1958 book Physics and Philosophy. “It introduced something standing in the middle between the idea of an event and the actual event, a strange kind of physical reality just in the middle between possibility and reality.”

In their paper, titled “Taking Heisenberg’s Potentia Seriously,” Kastner and colleagues elaborate on this idea, drawing a parallel to the philosophy of René Descartes. Descartes, in the 17th century, proposed a strict division between material and mental “substance.” Material stuff (res extensa, or extended things) existed entirely independently of mental reality (res cogitans, things that think) except in the brain’s pineal gland. There res cogitans could influence the body. Modern science has, of course, rejected res cogitans: The material world is all that reality requires. Mental activity is the outcome of material processes, such as electrical impulses and biochemical interactions.

Kastner and colleagues also reject Descartes’ res cogitans. But they think reality should not be restricted to res extensa; rather it should be complemented by “res potentia” — in particular, quantum res potentia, not just any old list of possibilities. Quantum potentia can be quantitatively defined; a quantum measurement will, with certainty, always produce one of the possibilities it describes. In the large-scale world, all sorts of possibilities can be imagined (Browns win Super Bowl, Indians win 22 straight games) which may or may not ever come to pass.

If quantum potentia are in some sense real, Kastner and colleagues say, then the mysterious weirdness of quantum mechanics becomes instantly explicable. You just have to realize that changes in actual things reset the list of potential things.

Consider for instance that you and I agree to meet for lunch next Tuesday at the Mad Hatter restaurant (Kastner and colleagues use the example of a coffee shop, but I don’t like coffee). But then on Monday, a tornado blasts the Mad Hatter to Wonderland. Meeting there is no longer on the list of res potentia; it’s no longer possible for lunch there to become an actuality. In other words, even though an actuality can’t alter a distant actuality, it can change distant potential. We could have been a thousand miles away, yet the tornado changed our possibilities for places to eat.

It’s an example of how the list of potentia can change without the spooky action at a distance that Einstein alleged about quantum entanglement. Measurements on entangled particles, such as two photons, seem baffling. You can set up an experiment so that before a measurement is made, either photon could be spinning clockwise or counterclockwise. Once one is measured, though (and found to be, say, clockwise), you know the other will have the opposite spin (counterclockwise), no matter how far away it is. But no secret signal is (or could possibly be) sent from one photon to the other after the first measurement. It’s simply the case that counterclockwise is no longer on the list of res potentia for the second photon. An “actuality” (the first measurement) changes the list of potentia that still exist in the universe. Potentia encompass the list of things that may become actual; what becomes actual then changes what’s on the list of potentia.

Similar arguments apply to other quantum mysteries. Observations of a “pure” quantum state, containing many possibilities, turns one of those possibilities into an actual one. And the new actual event constrains the list of future possibilities, without any need for physical causation. “We simply allow that actual events can instantaneously and acausally affect what is next possible … which, in turn, influences what can next become actual, and so on,” Kastner and colleagues write.

Measurement, they say, is simply a real physical process that transforms quantum potentia into elements of res extensa — actual, real stuff in the ordinary sense. Space and time, or spacetime, is something that “emerges from a quantum substratum,” as actual stuff crystalizes out “of a more fluid domain of possibles.” Spacetime, therefore, is not all there is to reality.

It’s unlikely that physicists everywhere will instantly cease debating quantum mysteries and start driving cars with “res potentia!” bumper stickers. But whether this new proposal triumphs in the quantum debates or not, it raises a key point in the scientific quest to understand reality. Reality is not necessarily what humans think it is or would like it to be. Many quantum interpretations have been motivated by a desire to return to Newtonian determinism, for instance, where cause and effect is mechanical and predictable, like a clock’s tick preceding each tock.

But the universe is not required to conform to Newtonian nostalgia. And more generally, scientists often presume that the phenomena nature offers to human senses reflect all there is to reality. “It is difficult for us to imagine or conceptualize any other categories of reality beyond the level of actual — i.e., what is immediately available to us in perceptual terms,” Kastner and colleagues note. Yet quantum physics hints at a deeper foundation underlying the reality of phenomena — in other words, that “ontology” encompasses more than just events and objects in spacetime.

This proposition sounds a little bit like advocating for the existence of ghosts. But it is actually more of an acknowledgment that things may seem ghostlike only because reality has been improperly conceived in the first place. Kastner and colleagues point out that the motions of the planets in the sky baffled ancient philosophers because supposedly in the heavens, reality permitted only uniform circular motion (accomplished by attachment to huge crystalline spheres). Expanding the boundaries of reality allowed those motions to be explained naturally.

Similarly, restricting reality to events in spacetime may turn out to be like restricting the heavens to rotating spheres. Spacetime itself, many physicists are convinced, is not a primary element of reality but a structure that emerges from processes more fundamental. Because these processes appear to be quantum in nature, it makes sense to suspect that something more than just spacetime events has a role to play in explaining quantum physics.

True, it’s hard to imagine the “reality” of something that doesn’t exist “actually” as an object or event in spacetime. But Kastner and colleagues cite the warning issued by the late philosopher Ernan McMullin, who pointed out that “imaginability must not be made the test for ontology.” Science attempts to discover the real world’s structures; it’s unwarranted, McMullin said, to require that those structures be “imaginable in the categories” known from large-scale ordinary experience. Sometimes things not imaginable do, after all, turn out to be real. No fan of the team ever imagined the Indians would win 22 games in a row.