Genes could record forensic clues to time of death

Dying, it turns out, is not like flipping a switch. Genes keep working for a while after a person dies, and scientists have used that activity in the lab to pinpoint time of death to within about nine minutes.

During the first 24 hours after death, genetic changes kick in across various human tissues, creating patterns of activity that can be used to roughly predict when someone died, researchers report February 13 in Nature Communications.

“This is really cool, just from a biological discovery standpoint,” says microbial ecologist Jennifer DeBruyn of the University of Tennessee in Knoxville who was not part of the study. “What do our cells do after we die, and what actually is death?”

What has become clear is that death isn’t the immediate end for genes. Some mouse and zebrafish genes remain active for up to four days after the animals die, scientists reported in 2017 in Open Biology.

In the new work, researchers examined changes in DNA’s chemical cousin, RNA. “There’s been a dogma that RNA is a weak, unstable molecule,” says Tom Gilbert, a geneticist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen who has studied postmortem genetics. “So people always assumed that DNA might survive after death, but RNA would be gone.”

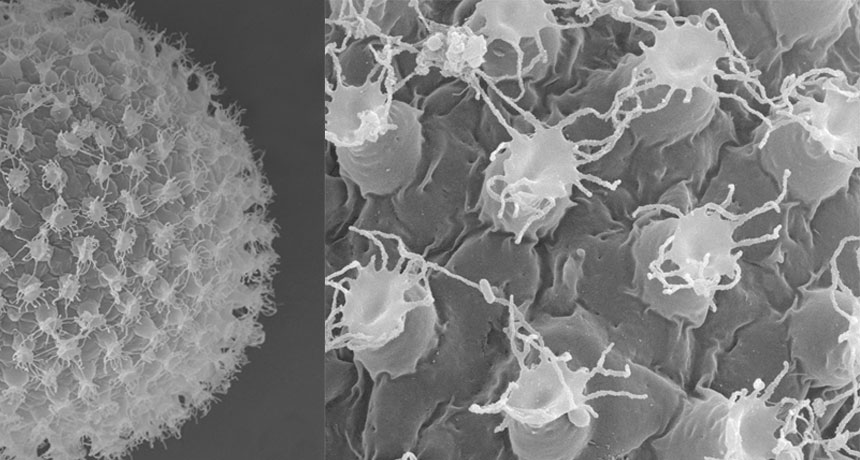

But recent research has found that RNA can be surprisingly stable, and some genes in our DNA even continue to be transcribed, or written, into RNA after we die, Gilbert says. “It’s not like you need a brain for gene expression,” he says. Molecular processes can continue until the necessary enzymes and chemical components run out.

“It’s no different than if you’re cooking a pasta and it’s boiling — if you turn the cooker off, it’s still going to bubble away, just at a slower and slower rate,” he says.

No one knows exactly how long a human’s molecular pot might keep bubbling, but geneticist and study leader Roderic Guigó of the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona says his team’s work may help toward figuring that out. “I think it’s an interesting question,” he says. “When does everything stop?”

Tissues from the dead are frequently used in genetic research, and Guigó and his colleagues had initially set out to learn how genetic activity, or gene expression, compares in dead and living tissues.

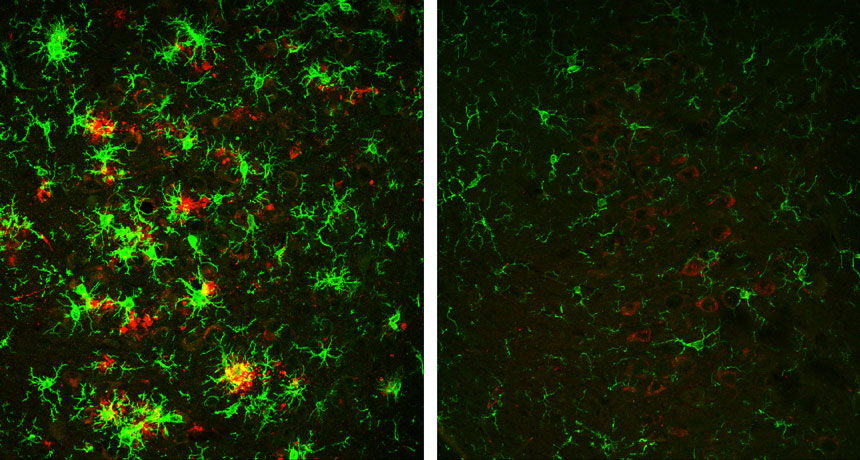

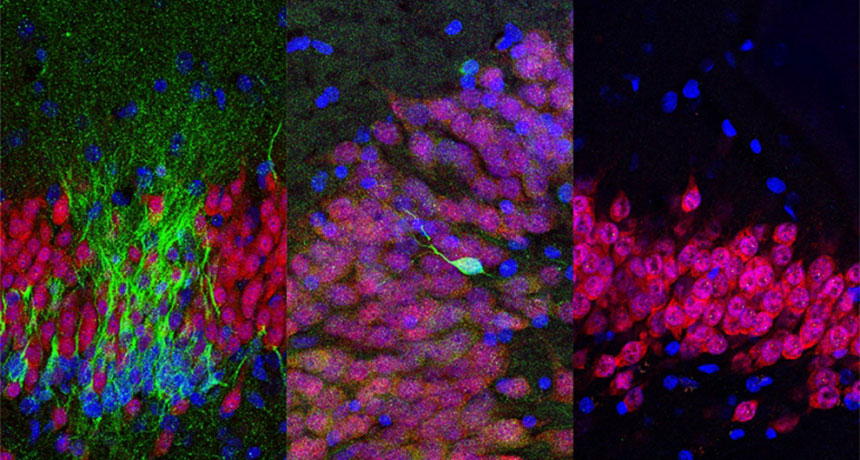

The researchers analyzed gene activity and degradation in 36 different kinds of human tissue, such as the brain, skin and lungs. Tissue samples were collected from more than 500 donors who had been dead for up to 29 hours. Postmortem gene activity varied in each tissue, the scientists found, and they used a computer to search for patterns in this activity. Just four tissues, taken together, could give a reliable time of death: subcutaneous fat, lung, thyroid and skin exposed to the sun.

Based on those results, the team developed an algorithm that a medical examiner might one day use to determine time of death. Using tissues in the lab, the algorithm could estimate the time of death to within about nine minutes, performing best during the first few hours after death, DeBruyn says.

For medical examiners, real-world conditions might not allow for such accuracy.

Traditionally, medical examiners use body temperature and physical signs such as rigor mortis to determine time of death. But scientists including DeBruyn are also starting to look at timing death using changes in the microbial community during decomposition (SN Online: 7/22/15).

These approaches — tracking microbial communities and gene activity — are “definitely complementary,” DeBruyn says. In the first 24 hours after death, bacteria, unlike genes, haven’t changed much, so a person’s genetic activity may be more useful for zeroing in on how long ago he or she died during that time frame. At longer time scales, microbes may work better.

“The biggest challenge is nailing down variability,” DeBruyn says. Everything from the temperature where a body is found to the deceased’s age could potentially affect how many and which genes are active after death. So scientists will have to do more experiments to account for these factors before the new method can be widely used.